|

In the early 2000s, I went to the NAWCC Museum in Columbia, PA with Bryan Girouard and Will Roseman. On display were several Hamilton Watches including Hamilton serial numbers #1,#2 & #3. It was an impressive sight #1 and #2 had NAWCC display tags that read either “Courtesy of the Hamilton Watch Company or on loan Hamilton Watch Company.” #3 was “on loan from another private collector.” The NAWCC featured these three watches on the cover of the October 2002 Bulletin, Vol 44/5 No. 340. In a 1979 publication from the NAWCC, an article was written that reads “Both serials No 1 and 2, can still be seen at your museum thanks to the Hamilton Watch Company permitting us to keep its collection on an indefinite loan. More than 4 dozen movements of various grades are in this loan.” In the original NAWCC brochure for the 225 Years of Timepieces it states that these were on loan from from May 1, 1979 Thru October 31, 1979, under the terms and abbreviations used, the letters “HWC” appear on this list and beside it states “Courtesy of the Hamilton Watch Company.” On page 46 of the brochure items 52 and 53 have (#1 & #2-HWC) in the paragraphs, describing them as “property of the Hamilton Watch Company.”

John Gelson who started with the Hamilton Watch Co in 1980 was the President/CEO of the Hamilton Watch Co from 1983 until 1990. After Mr. Gelson passed away in 2005, I was told that #1 and #2 belonged to him and they were still on display at the NAWCC Museum after his death. In 2018 a major auction house started selling several Hamilton and Illinois items from the estate of Mr. Gelson, historic one-of-a-kind items, and prototypes. All these items were from the historic Hamilton Archives. The Hamilton Archives watches were stored in a safe where HWC kept all of its historic watches Hamilton and Illinois made thru the years, several serial number 1’s, prototypes, R&D watches and others. Some never seen until that auction. I approached a Gelson family member and asked if they owned #1 and #2 and didn’t realize they were still on loan at the NAWCC. He said “no they only owned what was in the auction.” Curiously I approached a person familiar with the situation and I asked him if he knew about this as a board member of the NAWCC. He informed me that #1 and #2 are owned by the Hamilton Watch Co and on loan to the NAWCC and not part of the Gelson estate, and he personally knew the person who helped set up the original loan in 1979. He has subsequently changed his story and now says “Even my discussions with you over the years were significantly influenced by these incorrect cards.” In 2021, I was able to purchase the supporting documentation to the historic Hamilton archive documents. These explain how Mr. Gelson obtained all the HWC archive watches. In 1996 a group was hired to clean out the Wheatland Ave building (Hamilton Watch Co) and prepare it for sale. Mr. Gelson became a part of that group. There was a grey safe in the basement, locked as no one knew the combination and was taken to Mr. Gelson’s home. He hired a locksmith to open the safe and to his surprise it contained all the HWC & Illinois archive watches (plus others), also in the safe were 2 small 18 drawer cabinets that were part of the original green HWC archive safe. This document confirms that Gelson absolutely had no claim to Serial #1 or #2, or those other items still at the NAWCC museum. I kept researching the watches “on loan” at the NAWCC. In 2019, 2020 and 2021 I visited the Museum and saw a few items on display at the NAWCC that still read “On Loan Courtesy of the Hamilton Watch Co.” So I wrote a letter to the board of the NAWCC in August 2021 asking about items on loan at the NAWCC including a Hamilton Chronometer and two other items (Julie Nixon’s family watch and Art Zimmerla Adams and Perry Original Drawing) and their policy about notifying lenders their items are still on loan after several years. I asked for an audit of the” On loan items” as a lifetime member. The board’s response was a non-response. So I posted about it in the NAWCC forums and that conversation was shut down by the moderator, so I kept on it. I received three responses from board members and two stating they have researched all the museum documents and can’t find any loan agreements and that #1 and #2 belong to the NAWCC. I asked for the donation agreements, no reply was forthcoming, even though they have done so in the past on other watch. This led to a back and forth in emails with one coming from a board member that read, “We have thoroughly researched all the documents for the entire Hamilton collection. We have found no documentation of any "loaned" items. We did have some placards that were incorrectly written in regards to loaned items. Those were corrected for Hamilton items and some other items. NAWCC owns Hamilton serial #1 and serial # 2.” My reply: “So in your research, did you find a donation documents from the Hamilton Watch Co, or just no loan agreements? Can you share it? When did this all happen? I never saw it in any Bulletins. “ NAWCC Reply: “You had a number of questions and requests for the Board in August. Each of these were answered. You've since sent similar questions to me and other Board members, in addition to posting your questions on the Forums. The repetition of your questions has taken up additional time and resources and has duplicated efforts in responding to them. While I want to respect all member queries, I do not see any benefit in spending even more time on this same question when we have so many other matters to attend to. As far as I am concerned, your inquiry is settled and closed. I have instructed everyone on the Board and our staff to not devote any further time to this issue.” “Settled and closed” he says. Just like that, no apparent documentation of any donation agreement, the board just says, “they belong to the NAWCC,” just like that they can change the display cards and claim ownership. Just think about this, those display cards have been there some 42 years this way and now they decide to change them because I was asking questions? I am no lawyer, but apparently with zero proof of documentation and their claim seems to be a far stretch. I have been told by current members and past board members they have been “on loan.’ In any event, there you have it, the most important Hamilton Movements are being held with zero documented proof of a donation, just perhaps a self-serving email that states so and the changing of place cards stating so. Embarrassing and disappointing. In closing, who really owns #1 & #2 and those other items from the 1979 loan to the NAWCC? Anyone who collects watches knows about the Jaeger LeCoultre Reverso. Invented around 1930 by a combination of a few forward thinkers. When the Swiss watch collector César de Trey attended a polo match with an army military officer who had just broken his watch crystal in India, he asked de Trey to create a watch that could withstand the toughness of a polo match. He went to LeCoultre who then sought advice from Jaeger S.A. for the idea of a reversible watch. Jaeger S.A. then sent the idea to French designer René-Alfred Chauvot, the actual inventor of the slide and flip mechanism for the design. On Oct 10, 1933, the patent was granted (patent #1,930,416) and off they went.

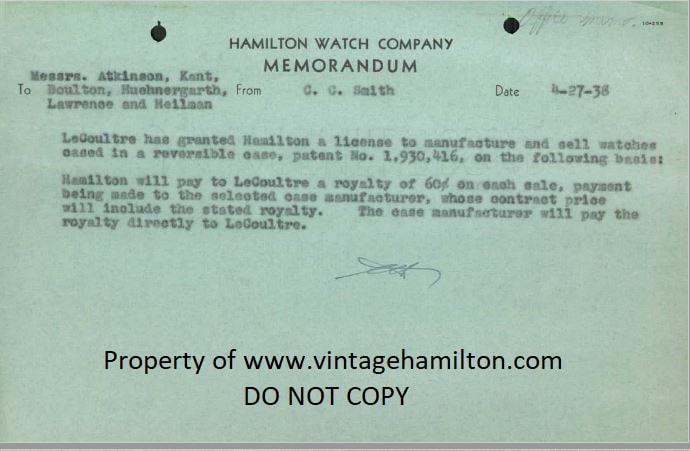

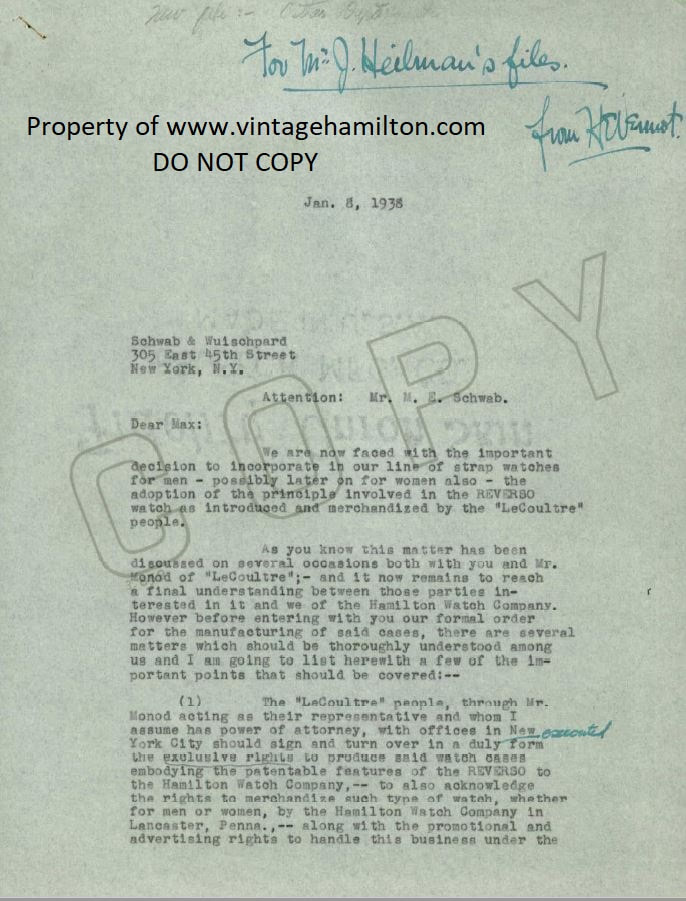

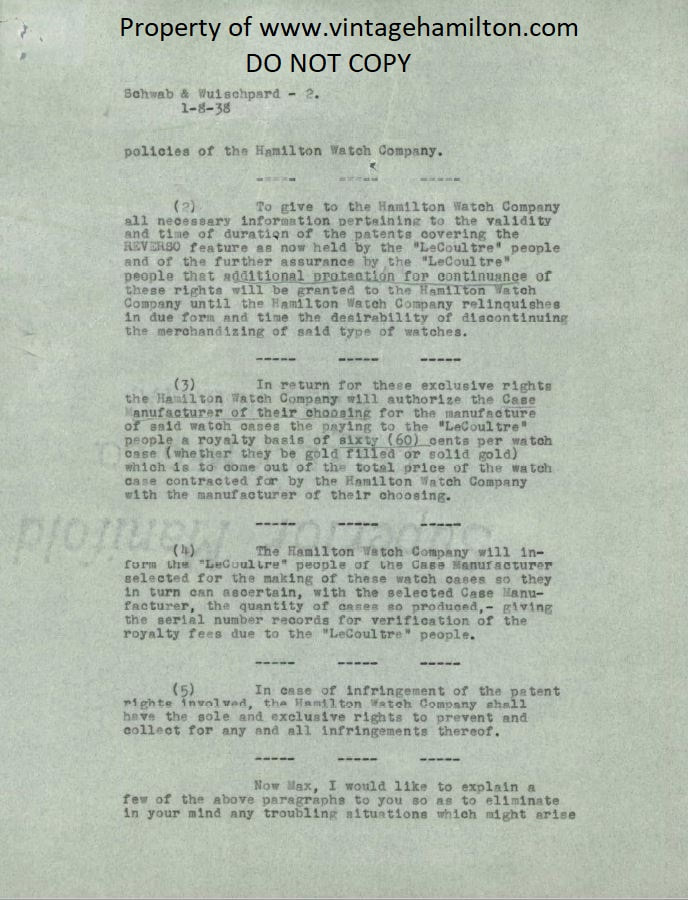

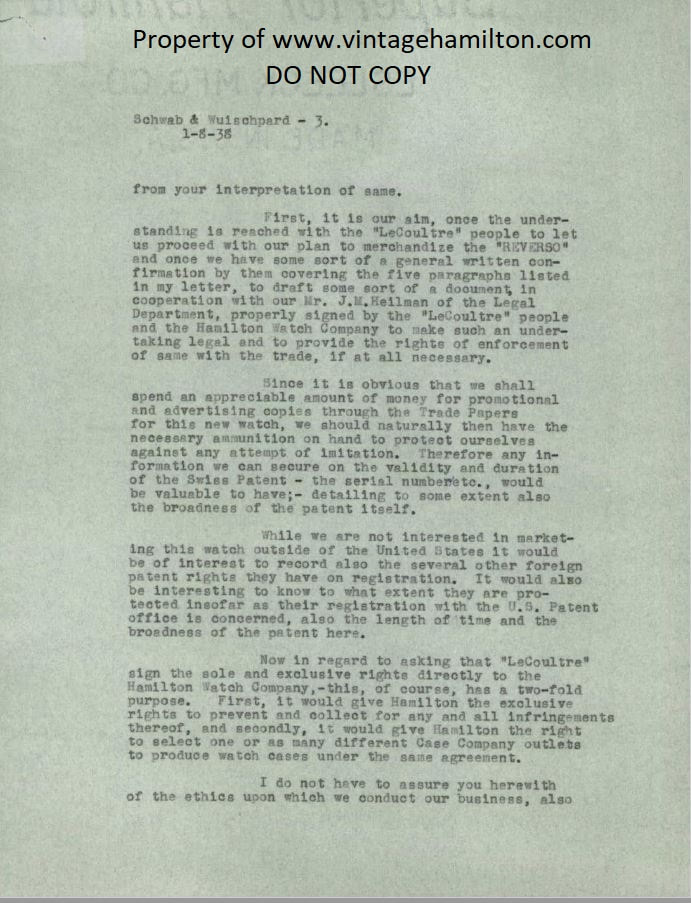

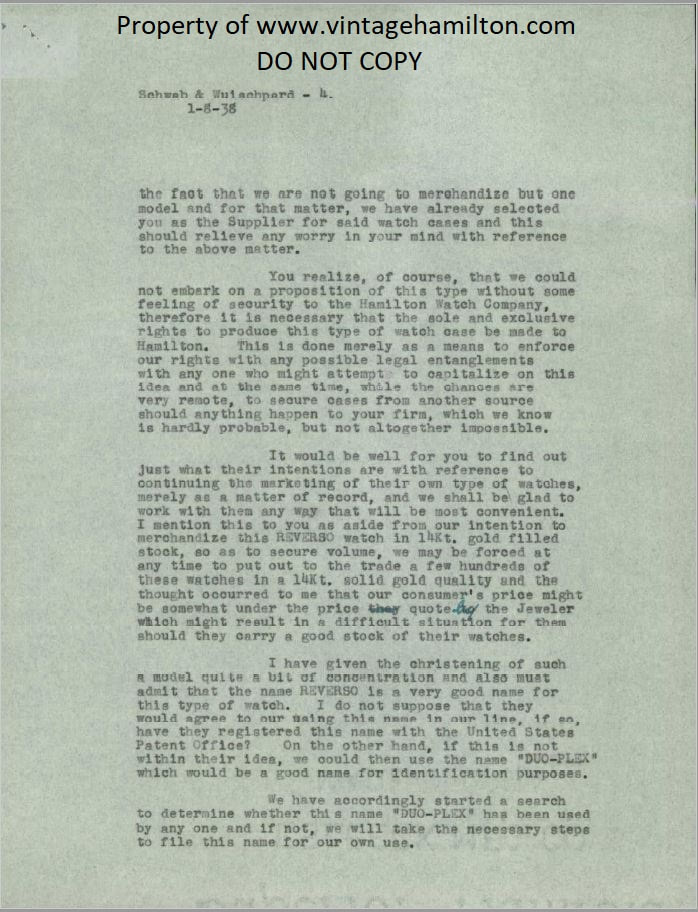

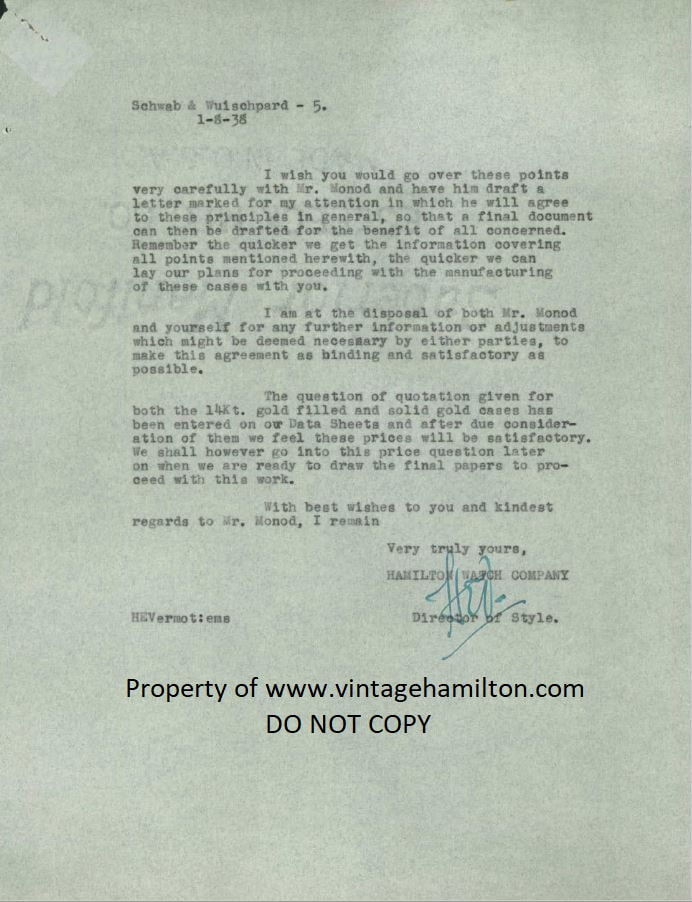

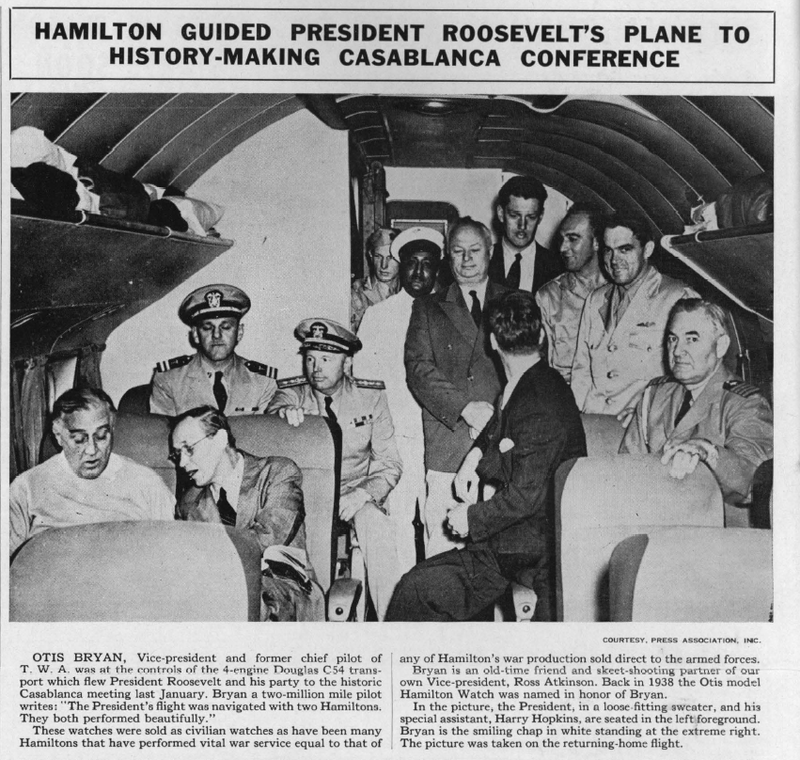

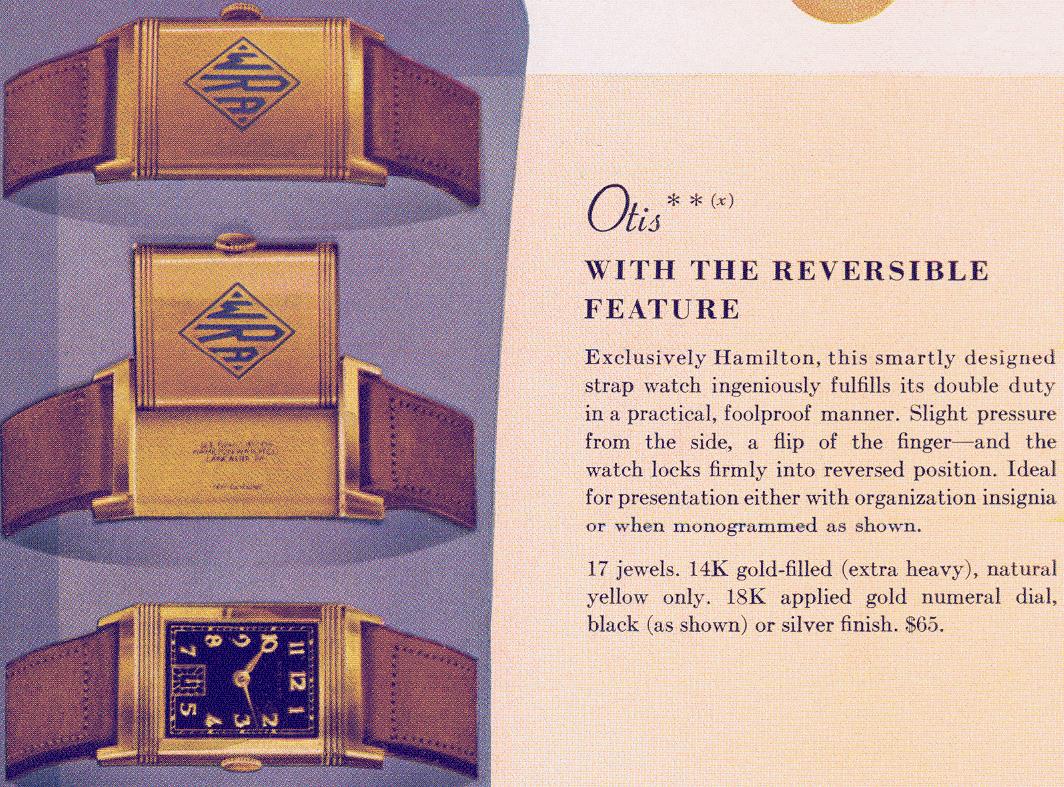

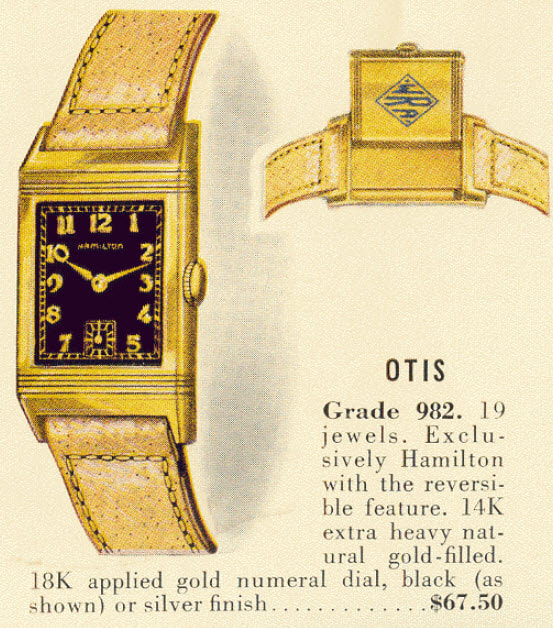

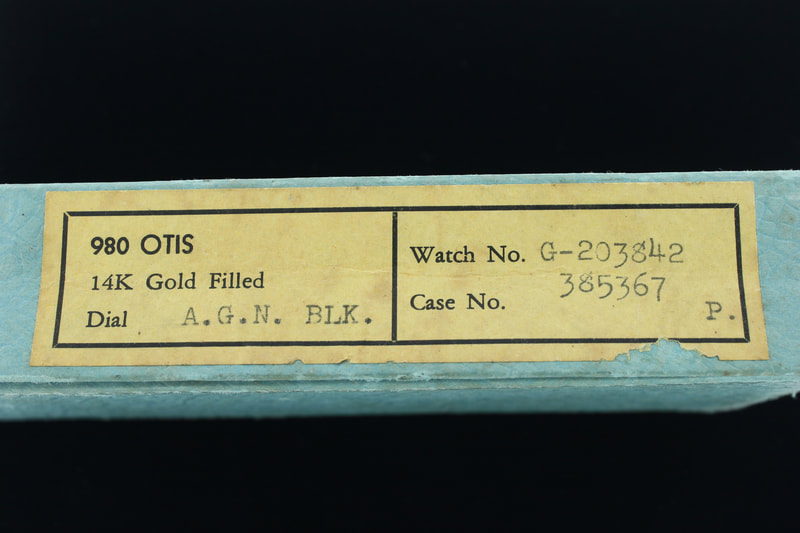

For years, the myth about the Hamilton Otis Reverso were heard by many. The urban myth was Hamilton copied the watch without permission from LeCoultre, were sued by Le Coultre and almost put out of business because of their flagrant patent infringement. People have told me they researched and found the lawsuit, others say they researched it and found nothing. To this day, when I buy an Otis, these stories are told to me. Just recently I was told by a seller about the Lawsuit. The rumor has always bothered me, as thru all my collecting years of Hamilton Watches, and through all my research about the company, Hamilton was a very corporate company, not one to steal patents, but rather they would purchase patents. I have seen this thru the research I have done about Hamilton Watch Co the past 40 years. I found check stubs of patents they have purchased back in the early 1900’s. Until a few years ago, the rumor was concrete and cast in stone. It wasn’t until I purchased a stash of Hamilton Co factory paperwork, all in all about four feet thick of it, that the truth came out. When I received all the paperwork, I went through most of it, including volumes of books on movements, blueprints, the making of the Marine Choronometer, production records and then I put it away. One day, my friend and fellow collector Bryan Girouard came to visit and asked if I had purchased anything interesting. I said sure, I got all this original paperwork from the Hamilton Factory. I said it’s too much to take in and read. He went looking thru the stack of papers and starting reading, and then he gave me this stare that I will never forget. He said and I quote “Do you know what you have in here?” I said yes, a bunch of great original files from the factory.” He said “yes you do, but you have the paperwork that shows Hamilton paid LeCoultre 60 cents per watch to use their patent in a licensing agreement.” We both shared a great laugh and debunked an urban myth that had lasted nearly 80 years. The fee did not change, it did not matter to LeCoultre if the watches were made in solid gold or gold filled, both models would pay a 60 cent per watch royalty fee to LeCoultre. On or around April 27, 1938, Hamilton was granted permission to use their patent (patent #1,930,416) to make a reversable watch (internal memo). Earlier on, on January 28, 1938, Hamilton Watch Co sent a letter to the casemaker of Schwab and Wuischpard (S&W) outlining what they wanted to produce with the conditions Lecoultre also presented and S&W could only make this watch for the Hamilton Watch Co. Hamilton named many of their watches after people. This watch was thought of being called the “Reverso” or the “Duo Plex,” but was eventually called the “Otis,” after Otis Byran, who was the Vice president and former chief pilot of T.W.A. Otis was a friend and skeet shooting partner of Ross Atkinson Hamilton Vice President in charge of sales, and in 1938, the Reverso was named the “Otis” after his friend. So there you have it my fellow watch collectors and friends, the myth is bogus and Hamilton did indeed have permission to use the Reverso Patent! |

Archives |